Babies conceived via in vitro fertilization (IVF) will have less genetic conditions than those conceived without IVF

There will be a divergence in the population, leaving those not conceived via IVF at a disadvantage.

In reproductive healthcare, a subtle shift is taking place—one that could potentially reshape the genetics of future generations. It’s not inconceivable that soon, children conceived through IVF will have fewer genetic conditions than children spontaneously conceived.

Traditionally, conversations surrounding IVF focus on its potential negative health impacts on children conceived via this method. Numerous factors come into play in this space: intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), cryopreservation of gametes and embryos, stimulation regimes, alongside factors related to the health and environment of those pursuing IVF, including age and genetics.

Many questions arise about which of these factors may contribute to various reported health outcomes in children, including low birth rate, birth defects, and even infertility itself. Concerning genetic issues, studies indicate an increased chance for methylation conditions, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann, to occur for those conceived via IVF.

However, here we investigate an alternative hypothesis, one in which those pursuing IVF are on the path to having children with fewer genetic conditions.

The Catalyst: Carrier Screening

The divergence begins with the widespread adoption of carrier screening, a tool available to anyone contemplating pregnancy. The point of carrier screening is to inform a person or couple if they have an increased chance to have a baby with select genetic conditions.

Carrier screening includes the assessment of hundreds of genetic conditions but not every genetic condition. If a person or couple are identified as carriers, then there may be a 25% or 50% chance to have a pregnancy with that condition. The kinds of conditions tested can vary in terms of the features or symptoms that the condition causes. Sometimes, the condition is life limiting, and there is no cure - other times, there is a diet or supplement that can be taken to mitigate symptoms of the condition.

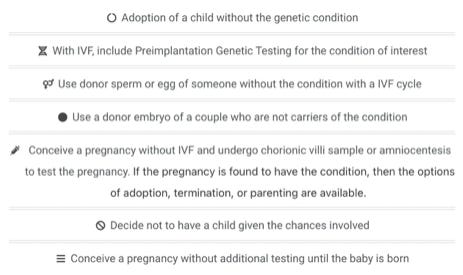

There are several reproductive options available when there is a known genetic risk including but not limited to prenatal diagnosis, preimplantation genetic testing, and testing of a baby after birth for the condition in question.

While carrier screening is open to all, those navigating IVF are more likely to embrace this option. The reasoning behind this lies in the fact it is presented during the preconception period. Those pursuing IVF can undergo this evaluation before a pregnancy even begins. This timing affords them a range of options not available to someone already pregnant, including preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), utilization of donor egg or sperm, or choosing not to have a child which could all reduce the likelihood of having a child with a genetic condition.

This is in contrast to those that spontaneously conceive, when carrier screening is often offered during pregnancy. There are still reproductive options available in pregnancy such as prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy, if the pregnancy is found to have the genetic condition. However, this option comes with great difficulty and is the only one in which prevention of the condition is possible, if that’s the goal of the family. Otherwise, if the pregnancy has the condition, then the child is born with it. While treatment for genetic conditions are coming down the pipeline, this is not yet the reality for all genetic conditions.

Ultimately, someone in the preconception period has the option to avoid having a pregnancy with the genetic condition they are carriers of by utilizing preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) in conjunction with in vitro fertilization. Given this option, those already pursuing IVF readily add PGT, thus are having fewer children born with genetic conditions compared to the population, who spontaneously conceive.

Let’s bring this decision to a more common life example - you’re going to a restaurant. At the hostess table, you are told you have the option to select one meal or to select the buffet option - you are provided a list of all foods available. The price is the same.

Some people are going to select the one meal for a number of personal reasons - they know what they like and don’t need options. Others are going to want the buffet option - not only do they get their favorite meal, but they also get to try other foods for the same cost.

Now, let’s imagine you have been seated in this restaurant without being provided the initial offer, have already ordered your favorite meal, and paid for it. The waitress comes over and now tells you that you can get the buffet for additional cost but only half of the buffet is available to you since you’ve already ordered a meal. At this point, some people may still opt to get the buffet. However, for others, they will feel like the additional options and cost aren’t worth it right now - they already made a decision and are anticipating their favorite meal.

When presented with all the options up front, more people are bound to utilize these choices, which is exactly the situation available to those utilizing IVF during the preconception period. They do not yet have a baby- they have not yet ordered their meal- and they have all the options, with none of the financial, emotional or social costs of an ongoing pregnancy.

There are, of course, those who choose to pursue carrier screening in pregnancy because they would like the opportunity to explore their reproductive options in the event they have an impacted pregnancy. Just like there are those, who are in preconception period, that opt out of carrier screening. However, these are more likely the exceptions, not the rule. Having more time to learn about the testing option and decide which reproductive option to pursue will create an environment for a greater uptake of carrier screening.

A Growing Disparity

As carrier screening gains prominence, a natural divergence in genetic outcomes unfolds. Those conceived through IVF, whose parents were armed with the knowledge gained from carrier screening, are poised for a future with fewer genetic conditions. Whereas those conceived spontaneously are more likely to be the children diagnosed with genetic conditions. Those with fewer genetic conditions will inevitably have healthier lives than those impacted by genetic conditions, resulting in a generational widening between the groups.

These disparities are most obvious geographically; first world access to IVF will widen the gap between developing and developed countries. Within developed countries, economic class variance will be exacerbated. Additionally, societies with greater religious fervor may deter use of IVF, widening the gap even further.

The Unfolding Future

As this divergence occurs, questions arise: Will there be a paradigm shift in our understanding and acceptance of genetic conditions? Will there be tolerance for those conceived with genetic conditions and available treatment? With greater recognition of genetic conditions though carrier identification, there may be camaraderie for those that have the conditions we are carriers of.

Alternatively, there may be the opinion the condition could have been avoided had the person’s parents pursued IVF with embryo screening to prevent the condition. Humans tend to view the world with an “us versus them” perspective. Will those accessing IVF and preventing of genetic conditions be another group that is treated differently, possibly favorably, given reduce medical costs associated with prevention of disease as opposed to treatment?

Considerations and Caveats

While this discussion outlines a potential future where those conceived via IVF have fewer genetic conditions, there are a number of complexities involved and other futures that may unfold. An important point to emphasize is the focus here is on inherited, monogenic conditions testable through carrier screening, omitting all other genetic conditions (i.e de novo autosomal dominant conditions, autosomal conditions/x-linked conditions not evaluated via carrier screening, mitochondrial conditions, polygenic conditions, multifactorial conditions, epigenetic traits, etc).

We’ve explored a surface level consideration of a potential divergence between those conceived via IVF and via spontaneous conception. Instead, this divergence can be squashed if carrier screening was offered in the preconception period with or without IVF more frequently than during pregnancy as is common practice in 2024. Another story may unfold if that were to be the case.